Closing the Loop, Turning Responsibility Into a Resource

Waste is the mirror of how a society designs, consumes, and cares for its environment and people. Globally, municipal solid waste has reached about 2.3 billion tonnes per year in 2025 and is projected to climb to around 3.8–3.9 billion tonnes by 2050 if systems do not change, with at least a third currently mismanaged through open dumping or burning. Landfills and dumps are a major source of methane—around 20% of global methane emissions—which is about 80 times more powerful than CO₂ over 20 years, making waste a critical climate issue as well as a health and justice issue.

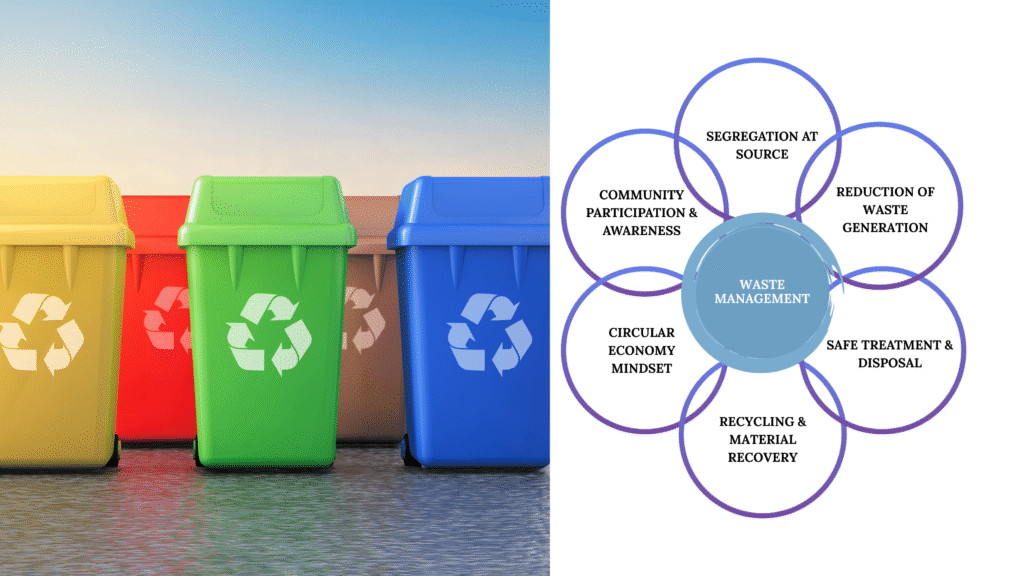

Waste management – closing the loop

In natural ecosystems, outputs from one process become inputs for another; nothing is “thrown away”. Modern human systems break this loop by extracting resources, using them briefly, and discarding them as pollution. A sustainable society aims to redesign this pattern so that materials circulate safely and continuously.

This requires acting across the full lifecycle of products—how they are designed, produced, used, repaired, and eventually transformed—not just at the moment the bin is filled. The strongest rule remains: “Waste is not a thing; it is a design error.”

Six interlinked factors can guide communities and institutions.

Six key factors of responsible waste systems

- Segregation at source

- Waste becomes manageable only when separated correctly where it is generated (home, school, market, office).

- Practical steps: at least three basic streams—organic (wet), recyclables (dry), and hazardous/e-waste—using clear containers, labels, and simple instructions. Proper source segregation greatly reduces landfill methane and contamination of recyclable.

- Reduction of waste generation

- Stopping waste before it exists is more effective than any recycling system.

- Practical steps: avoid single-use items, over-packaging, and disposable products; promote sharing, renting, and product-as-a-service models (e.g., tool libraries, refill shops).

- Safe treatment and disposal

- Some residual waste will remain even in advanced systems and must be managed to protect soil, water, and air.

- Practical steps: engineered landfills (not open dumps), controlled handling of hazardous and biomedical waste, and strict bans on open burning, which releases toxic gases and particulates.

- Recycling and material recovery

- Recycling saves raw materials and energy and can reduce pollution from mining and manufacturing.

- Practical steps: local collection points; clean sorting lines; extended producer responsibility schemes where manufacturers help finance collection and recycling; support for informal workers who already recover materials.

- Circular economy mindset

- Products and packaging should be designed so they can safely return as nutrients (biological cycle) or be reused, repaired, or remanufactured (technical cycle).

- Practical steps: eco-design standards, take-back schemes, repairability scores, and industrial symbiosis where one process’s by-product becomes another’s input.

- Community participation and awareness

- Even the best infrastructure fails if people do not use it correctly.

- Practical steps: ongoing education in schools and neighborhoods, clear communication about collection schedules and rules, and participatory design of local systems, so people feel ownership.

Why proper waste management matters now

Without responsible handling, rising waste streams lead to:

- Polluted air (open burning and poorly controlled incineration release toxic gases and fine particles).

- Contaminated soil and groundwater (leachate carrying heavy metals, chemicals, and pathogens).

- Polluted rivers and oceans (plastic leakage to aquatic environments estimated at tens of millions of tonnes and projected to increase if trends continue).

- Biodiversity loss (animals ingesting or entangled in plastics and other debris).

- Disease spread (mosquitoes, rodents, and pathogens thriving in unmanaged dumps).

- Climate impacts (landfills and dumps emitting significant methane and some nitrous oxide).

Proper waste management supports human health, safe drinking water, productive soils, livable cities, and protection of future generations.

Types of waste – and why management matters more than volume

Different waste streams require different strategies:

- Organic / biodegradable (food scraps, garden waste)

- Landfilled organics decompose anaerobically, producing methane; in many cities, 40–60% of municipal solid waste is organic.

- Composting, vermicomposting, and anaerobic digestion turn this into soil amendments and biogas, reducing emissions and improving soil.

- Recyclable (paper, plastics, metals, glass)

- Recycling saves energy and raw materials (e.g., recycling aluminum saves up to 95% of energy compared with primary production).

- Contamination from mixed or dirty waste greatly reduces recyclability, so source segregation is crucial.

- Hazardous waste (batteries, paints, chemicals)

- Must be collected separately and handled in specialized facilities to avoid persistent contamination and health damage.

- E-waste (phones, computers, appliances)

- Contains valuable metals but also toxic substances; “urban mining” of e-waste is a growing strategy to recover resources while avoiding unsafe informal recycling.

- Biomedical and industrial waste

- Requires strict controls and tracking to prevent infections and large-scale pollution; ideally treated near the source.

- Construction and demolition waste

- Large volume but often recyclable (aggregates, metals, timber); selective demolition and on-site sorting make reuse and recycling much easier.

Impact is determined less by absolute quantity than by how systematically and safely each stream is managed.

Global progress and examples

Global data show waste generation rising faster than population and sometimes faster than GDP, but also highlight promising models:

- Sweden

- Recovers or recycles about 99% of household waste through a combination of high recycling rates and waste-to-energy, drastically reducing landfill use.

- Kamikatsu, Japan

- Over 80% recycling rate with 40+ segregation categories, a community “bring system” and strong local engagement—seen as a zero-waste role model.

- Germany and EU (Green Dot, EPR)

- Extended producer responsibility schemes make producers pay for packaging collection and recycling, encouraging eco-design and lighter packaging.

- South Korea (Seoul)

- “Pay-as-you-throw” food waste policies cut waste and support large-scale composting and biogas production.

- San Francisco (USA)

- Legal requirements for composting and recycling, with city-wide collection and processing, pushed diversion rates significantly upward.

- Kerala (India)

- Moves toward decentralized, household-level organic waste treatment, reducing pressure on landfills and dumps.

These cases show that when governments provide supportive policy and infrastructure, and communities actively participate, waste can become a managed resource rather than a growing crisis.

Future directions – from waste disposal to resource intelligence

Emerging trends point toward systems where the very concept of waste shrinks:

- Zero-waste cities, homes, and shops

- Bulk, refill, and package-free retail; bans on some single-use plastics; strong repair and reuse culture.

- Bio-based and fully compostable materials

- Packaging, textiles, and some electronics made from materials that safely biodegrade or can be industrially composted, reducing long-lived pollution.

- AI and robotics for sorting

- Automated systems in material recovery facilities to improve sorting quality and reduce human exposure to hazards.

- Plastic-degrading microbes and enzymes (still early-stage)

- Biological methods to break down certain plastics more safely and quickly, combined with strong reduction measures.

- Urban mining and industrial symbiosis

- Systematic recovery of metals and critical minerals from e-waste and industrial residues; linking industries so that by-products flow from one to another.

- Digital sharing and repair platforms

- Tools, clothing, electronics, and other goods shared, rented, or repaired instead of owned and quickly discarded.

The direction is clear: the long-term goal is not simply “better waste management” but material systems where harmful waste is designed out.

How to contribute to this component

You can help turn this Waste Management component into a practical, evolving guide by:

- Starting or documenting local compost units, repair cafés, tool libraries, or small recycling centres and sharing what works and what does not.

- Mapping your community’s waste flows (what types, how much, where they go) to identify priority interventions.

- Working with schools, markets, and neighborhood groups to create simple segregation rules and visible examples.

- Collecting and sharing policy ideas and case studies—from zero-waste towns to extended producer responsibility laws—that other communities can adapt.

Every step toward reducing, reusing, segregating, and safely treating waste helps close the loop—and makes human activity more compatible with the cycles of nature.