Safety and resilience are the immune system of a community: they do not prevent every shock, but they determine how well people anticipate, absorb, and recover from crises. Experience from recent disasters and pandemics shows that communities with good planning, strong social ties, and clear communication save more lives and rebuild faster than those that rely only on formal institutions.

Safety & resilience – preparing for the unexpected

Resilience is not just about surviving disasters; it is about staying functional and humane under stress and emerging with lessons learned. It combines physical measures (infrastructure, supplies, technology) with social and psychological strengths (trust, solidarity, coping skills).

A resilient community prepares for risks it can foresee—storms, floods, heatwaves, earthquakes, fires, disease outbreaks, cyberattacks—but also builds flexible systems that can respond to surprises. This preparation must be inclusive, protecting children, elders, people with disabilities, and those with fewer resources, so no one is left behind.

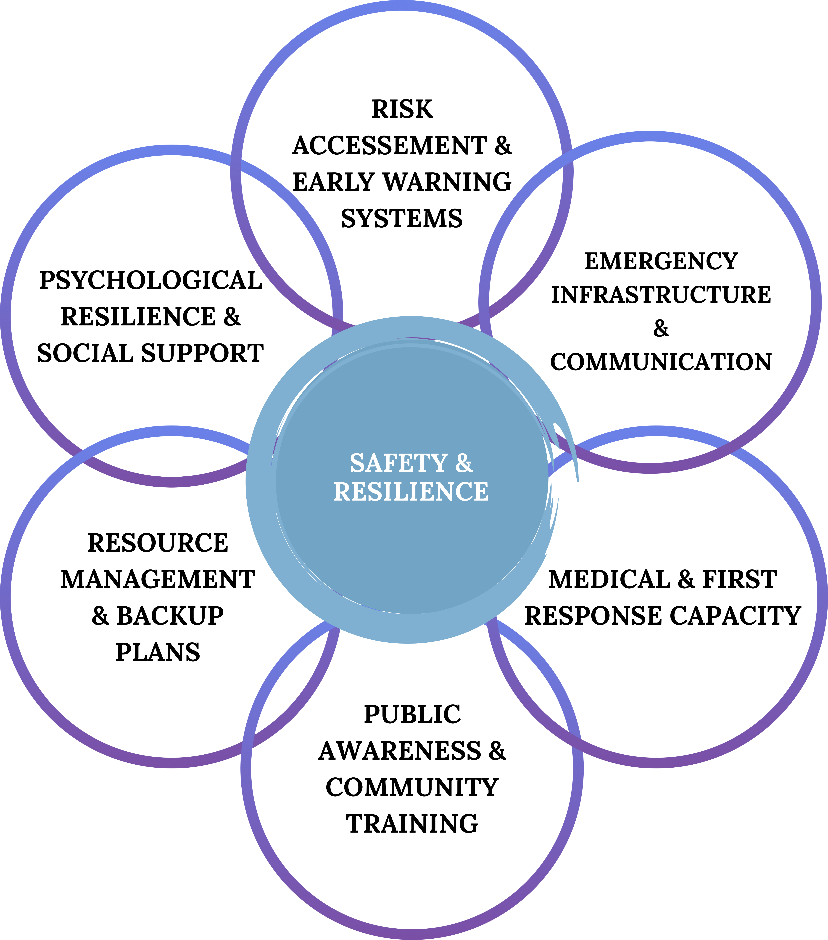

Six core factors of safety and resilience

- Risk assessment and early warning systems

- Map local vulnerabilities: floodplains, landslide zones, fire-prone areas, industrial hazards, and digital or cyber risks.

- Develop early warning systems for weather, air quality, health alerts, and digital threats, and make sure alerts reach everyone (sirens, SMS, radio, loudspeakers, community volunteers).

- Emergency infrastructure and communication

- Prepare safe shelters, evacuation routes, backup power and water, and emergency logistics for food and medicines.

- Establish multiple communication channels—local radio, notice boards, messaging groups, and trusted community coordinators—to reduce confusion during crises.

- Medical and first response capacity

- Ensure availability of trained first responders, ambulances, basic trauma care, and essential medical supplies.

- Create clear protocols for triage, referral to hospitals, and coordination between health services, fire, police, and community volunteers.

- Public awareness and community training

- Teach basic preparedness to everyone: what to do in floods, fires, earthquakes, disease outbreaks, or digital scams.

- Run regular drills in schools, workplaces, and neighbourhoods so actions become familiar, not improvised in panic.

- Resource management and backup plans

- Maintain reserves of clean water, food, essential medicines, lighting, and alternative power systems for critical services.

- Prepare relocation and support plans for people who may need temporary shelter or assistance if their homes or livelihoods are affected.

- Psychological resilience and social support

- Recognize that disasters strain mental health; fear, grief, and uncertainty are normal but need support.

- Encourage peer support groups, access to counselling where possible, and spaces where people can share experiences and emotions without stigma.

Why preparedness matters

Preparedness does not eliminate danger, but it changes outcomes:

- Reduces loss of life and serious injury by enabling faster, calmer responses.

- Limits damage to homes, infrastructure, and livelihoods through better siting, construction, and contingency plans.

- Prevents chaos and panic by providing clear roles, communication, and trusted leaders.

- Strengthens confidence, solidarity, and trust within communities, which in turn lowers the risk of violence, exploitation, or scapegoating.

- Speeds recovery and reduces long-term suffering, especially for vulnerable groups.

Preparedness turns fear into clarity, and helplessness into coordinated action.

Types of disasters and how to prepare

Natural hazards

- Climate and weather (floods, storms, heatwaves, droughts):

- Monitor forecasts and early warnings, identify safe shelters, design local evacuation and cooling strategies, and protect critical infrastructure from flooding or overheating.

- Geological (earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, volcanic eruptions):

- Use appropriate building codes, avoid construction in highest-risk zones, and practice evacuation and assembly drills.

- Biological (epidemics and pandemics):

- Maintain surveillance, hygiene education, protective equipment, and continuity plans for schools and workplaces; use remote communication and telemedicine where possible.

- Wildfires and urban fires:

- Maintain defensible space around buildings, safe electrical wiring, firebreaks, hydrants, and trained volunteers to support fire services.

Human-caused and technological hazards

- Industrial accidents (chemical leaks, explosions):

- Strict safety standards, emergency shut-off systems, and rapid public notification and shelter instructions.

- Transport incidents (road, rail, air, and maritime accidents; oil or chemical spills):

- Enforcement of safety standards, clear emergency response routes, and environmental protection plans.

- Cyber and digital threats (hacking, data loss, infrastructure interference):

- Basic cybersecurity hygiene, backups of critical data, strong access controls, and awareness training for users.

- Conflict and violence (unrest, terrorism, targeted attacks):

- Early dialogue and mediation systems, protection of vulnerable sites, safe shelters, and coordination between authorities and communities.

Preparedness is not about living in fear of worst cases; it is about showing respect for life by planning for them.

Individual and community training for resilience

Even a few hours of training can dramatically increase a person’s ability to help in a crisis. Useful training areas include:

- Basic first aid and CPR: treating bleeding, fractures, burns, and performing resuscitation until professional help arrives.

- Fire safety and evacuation: safe use of extinguishers, clear exit routes, and drills in homes, schools, and workplaces.

- Light search and rescue: safely checking buildings, helping trapped or injured neighbours, and knowing when not to enter dangerous structures.

- Personal safety and self defence awareness: risk avoidance, de escalation, and safe escape strategies.

- Psychological first aid: offering calm presence, listening, and simple support to people in distress.

- Crisis communication and local leadership: making decisions under pressure, delegating tasks, and keeping information clear and consistent.

When many people share these skills, response becomes faster, fairer, and less dependent on a few professionals.

Lessons from history and recent crises

Past disasters highlight consistent patterns:

- Communities that prepared together—through local plans, drills, and mutual aid networks—experienced fewer casualties and recovered more quickly.

- Early warning systems, combined with clear communication and trusted leadership, often saved more lives than physical infrastructure alone.

- Ignoring scientific signals about climate, health, or structural risks led to higher damages and repeated avoidable tragedies.

- Strong social bonds reduced panic, looting, and violence, while fragmented communities struggled to coordinate and protect vulnerable members.

- Post disaster recovery was faster and more equitable where there was mutual support, transparent decision making, and inclusive planning.

Resilience is built long before a disaster; the event merely reveals how strong or fragile systems and relationships already are.

How to contribute to this component

You can help strengthen this Safety & Resilience base by:

- Offering or organizing first aid, CPR, fire safety, or basic rescue training in your community.

- Helping to map local risks and co create simple, visual emergency plans for neighbourhoods, schools, and workplaces.

- Sharing examples of past crises in your area—what worked well, what failed, and what has changed since.

- Contributing designs or ideas for low cost early warning systems, backup energy and water solutions, or community support networks.

When people learn to protect themselves and each other, safety and resilience become shared responsibilities, not just the task of distant institutions.