Transport is the circulatory system of modern society: it connects people to jobs, food, health care, and each other, but it also generates around one-fifth of global CO₂ emissions and a large share of urban air and noise pollution. Future-ready mobility must therefore put people, health, and the climate first—shifting from “moving vehicles” to “moving people and goods efficiently, fairly, and cleanly.”

Mobility – moving smart, green, and fair

Transport today is a major pressure point on the planet and on public health. Road and other transport activities account for roughly 23% of global energy-related CO₂ emissions, with about three-quarters of transport CO₂ coming from road vehicles (cars, trucks, buses). These emissions drive climate change, while exhaust fumes and tire dust contribute to respiratory disease and environmental degradation.

Yet the same system can be redesigned to deliver massive health and climate gains. Studies show that better walking and cycling infrastructure, along with more compact, transit-oriented cities, could cut urban transport emissions by 2–10% and yield hundreds of billions of dollars per year in health benefits through reduced heart disease, diabetes, and premature deaths.

A good mobility system is one where it is easy, safe, and affordable to walk, cycle, and use public and shared transport—and where private motorized travel is clean, efficient, and used where genuinely needed.

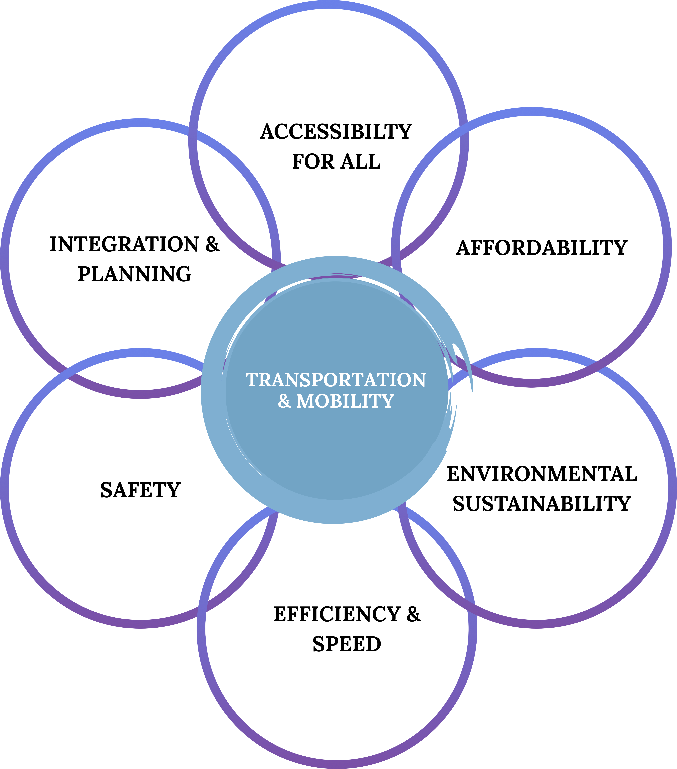

Six core factors for sustainable mobility

- Accessibility for all

- Everyone—children, elders, people with disabilities, low-income groups—should be able to reach basic services (schools, clinics, markets, workplaces) safely and affordably.

- Practical steps: barrier-free sidewalks and crossings, low-floor buses and trams, audio-visual information in vehicles and stations, and pricing that does not exclude low-income users.

- Environmental sustainability

- Transport must reduce greenhouse gases, air pollutants, noise, and land take. In many regions, transport emissions are still rising faster than other sectors, especially in fast-growing cities.

- Practical steps: electrify vehicles (buses, two-wheelers, cars) where power is decarbonizing; prioritize public transport and active modes; phase out the most polluting engines; redesign streets to reduce car dependence.

- Affordability

- Mobility should open opportunity, not trap households in high costs for fuel, fares, and vehicle ownership.

- Practical steps: integrated ticketing and caps, subsidies or “mobility passes” for vulnerable groups, support for affordable e-bikes and shared schemes rather than private car ownership alone.

- Efficiency and speed

- Travel time affects jobs, education, care work, and social life. Transport that is fast for some but traps others in long, unreliable commutes deepens inequality.

- Practical steps: bus rapid transit (BRT), dedicated bus and bike lanes, traffic signal priority for public transport, and compact “15-minute” neighborhoods where many needs are within walking or cycling distance.

- Safety

- Road traffic injuries are a major cause of death worldwide; many are preventable with safe system design.

- Practical steps: lower speed limits in residential areas (e.g., 30 km/h), safe crossings, protected bike lanes, traffic calming, and strong enforcement of drunk driving and distracted driving rules.

- Integration and planning

- Walking, cycling, buses, metros, trains, shared mobility, and freight must work as one coordinated network.

- Practical steps: mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) platforms that combine modes into one app/payment, secure bike parking at stations, synchronized timetables, and land use planning that reduces the need for long trips.

The best systems are people-first: streets are designed as public spaces for living, not just traffic corridors.

Environmental and health impacts

Transport affects climate, ecosystems, and health in multiple ways:

- Climate and air quality

- CO₂ and other pollutants (NOₓ, SO₂, PM) from combustion engines contribute to global warming and respiratory illnesses. Road transport alone accounts for about 15% of global CO₂ emissions.

- Noise and stress

- Constant traffic noise raises stress and can disturb sleep and wildlife patterns, especially near major roads and airports.

- Space, land, and biodiversity

- Large road networks, parking lots, and runways consume land, fragment habitats, and contribute to urban heat islands through extensive asphalt and concrete.

- Microplastics and tire dust

- Tire wear and brake dust release particles and microplastics into air, soil, and water; even electric vehicles still cause this non-tailpipe pollution.

On the positive side, walking and cycling emit virtually no CO₂ or harmful pollutants, use minimal road space, and integrate physical activity into daily life, significantly reducing risks of heart disease, diabetes, and premature mortality. Making these modes safe and attractive is one of the highest-leverage health and climate actions cities can take.

Modes of transport – building a balanced mix

Different modes have different strengths; no single option is best everywhere. A resilient system uses a thoughtful combination:

- Walking

- Best for short trips; zero emissions; highest community interaction; foundational for 15-minute cities.

- Needs safe, shaded, continuous sidewalks and crossings to be viable year-round.

- Cycling and micromobility (bikes, e-bikes, scooters)

- Fast and efficient for short to medium distances; low operating cost; tiny space footprint.

- Requires protected lanes, secure parking, and rules for safe, non-obstructive parking of shared devices.

- Public transport (buses, BRT, metro, tram, rail)

- High capacity, low emissions per passenger, crucial for medium to long distances and dense corridors.

- Needs frequent, reliable service and comfortable, safe stations to attract users.

- Shared and flexible services (car-sharing, ride-sharing, on-demand shuttles)

- Increase vehicle occupancy and reduce parking needs, especially in cities.

- Most effective when integrated with public transport and regulated to avoid congestion and empty “deadheading” trips.

- Private motor vehicles (cars, motorbikes)

- Offer flexibility, especially in rural and low-density areas, but create congestion, emissions, and unsafe conditions when overused.

- Electric vehicles remove tailpipe emissions and improve local air quality, but still rely on clean electricity and responsible battery supply chains.

- Long-distance modes (rail, buses, aviation, shipping)

- Electric and high-speed rail can offer low-carbon alternatives to short-haul flights; aviation remains the most carbon-intensive passenger mode per kilometre.

Where mobility is heading – and what communities can do

Trends for the next decade point to cleaner, more connected, and more shared mobility, but the outcomes will depend on policy choices:

Key global directions:

- Electrification

- Rapid growth of electric cars, buses, two-wheelers, and delivery fleets, supported by expanding charging infrastructure and stronger emissions standards.

- Climate benefits are greatest where the power grid is also decarbonizing.

- Active and compact cities

- Movement toward “15-minute cities”, traffic-calmed zones, and large-scale investments in cycling and walking infrastructure, proven to reduce emissions and healthcare costs.

- Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS)

- Integrated digital platforms that combine public transport, micromobility, car-sharing, and taxis into simple, app-based services, reducing the need for private car ownership.

- Data-driven planning and smart infrastructure

- Use of sensors and AI for adaptive traffic signals, real-time route information, and optimized public transport routes, improving reliability and reducing congestion.

Practical steps communities can take now:

- Reallocate street space: add protected bike lanes, widen sidewalks, create low-speed zones and car-free streets around schools and markets.

- Improve and prioritize public transport: dedicated bus lanes, better stops, integrated fares, real-time information.

- Support e-bikes and shared bikes/scooters: docking stations near transit hubs, safe parking, and clear rules.

- Plan land use and mobility together: avoid new developments that can only be reached by car; cluster housing near transit.

- Encourage cleaner fleets: electrify municipal buses and service vehicles first; introduce incentives and standards for taxis and delivery fleets.

- Engage residents: co-design local mobility plans through workshops, surveys, and pilots (e.g., “pop-up” bike lanes, temporary street closures) before making permanent changes.

How to contribute to this component

You can enrich this Transportation & Mobility base by:

- Sharing local examples of successful changes (new bike lanes, safer crossings, improved bus routes) and their effects on safety, emissions, and daily life.

- Proposing eco-mobility pilots such as e-bike libraries, school streets, or neighborhood car-sharing.

- Documenting health and environmental impacts of current mobility patterns in your community (air quality, noise, crash statistics, commute times).

- Helping design educational materials or campaigns on safe walking, cycling, shared transport, and the benefits of reducing car dependence.

Together, these contributions can help communities move toward mobility systems that are clean, safe, fair, and deeply supportive of human health and freedom.